Ten tips from the psych ward

What a year it’s been. I’m not the only one feeling it. In Ontario, hospitals were experiencing a surge in mental health inpatient admissions as early as the summer. So, I’m going to share ten tips for navigating inpatient mental health care for anyone heading to the ward (voluntarily or otherwise) for the first time this holiday season. I’ve learned from my multiple hospital stays that seeking out crisis care isn’t pleasant, but the advice below can make inpatient care much more comfortable, which can make the experience less jarring.

Bring slippers and ask for two gowns

No shoelaces in the ward, baby. They’re a self-harm risk (but the long ties on your hospital gown are safe). Bring your own slippers if you don’t want to shuffle around in whatever sad papery excuse for footwear your local hospital provides. Bonus points if you remember flip-flops for the communal showers. Oh, and circling back to the gowns for a moment: ask for two. One to tie on forward and one backwards. Unless you don’t mind a breeze on the bum.

Bring quarters. Write down important phone numbers

While there are certain units that allow patients to keep their cellphones, I’ve never been to one. Instead, each ward boasted payphones that looked as rough as the few remaining ones that can be found on the outside world. Because you’ll be parted with your gizmo (and it’s not 1980 anymore so no one has phone numbers memorized) write them down to bring with you to the hospital. And bring change. You’ll want contact with the outside world.

Prepare for the possibility of constipation

Everybody poops. That is, everybody poops until they’ve been eating hospital food for an extended period of time. I’ve yet to eat a hospital dish that tasted like anything at all (think airplane food, but don’t expect any salt), yet somehow the over-boiled and bland food, in concert with side effects from psychotropic drugs, has an impressive ability to bind one’s bowels. I’ve seen many fellow patients taken down by a plugged pooper. To be fair, it doesn’t exactly take a roaring intellect to determine why there’s so much digestion trouble in inpatient mental health units: on a vegetarian meal plan, I once ate cheese sandwiches for five days straight.

Behave yourself

Remember that studious kid in elementary school who was always top of their class, followed all the rules, and never bothered their teacher? Be that kid in the psych ward. Yes, there will be times when you’ll get so frustrated by anything from fellow patients to medical incompetence that you’ll just want to smash in someone’s teeth. And yes, it’s unfair that during a mental health crisis you’re expected to be inherently familiar with inpatient routines and how to navigate the system, but the better you behave the more privileges you’ll get early on—things like smoke breaks, being allowed to use metal cutlery, monitored passes, and the holy grail, unmonitored passes—and the more comfortable your stay will be.

Vouch for yourself

This piece of advice may seem at odds with the last one but occasions will arise during psychiatric care when you’ll absolutely need to vouch for yourself. For example, during my second hospital stay, I went up to the nurses’ window to get my morning medication at the same time as a patient named Amanda. The nurse mixed up our meds. I noticed pretty quickly that the pills in my small paper cup weren’t the usual ones and pointed it out—Amanda, meanwhile, had thrown my pills back dry. Despite both Amanda and I wearing hospital braces stamped with our name and an individual barcode, it took 30 minutes of arguing with the nurse before I got the correct medication. No one trusts you less than when you’re in inpatient psychiatric care.

Don’t get stoned during your day pass

Oh, how thrilled I was to receive my first unmonitored day pass about a week into my second hospitalization. I had three hours of freedom from fishbowl drama, regimented smoke breaks, and cheese sandwiches. I practically ran back to my apartment. When I arrived, I shoved my face into both of my cats. I missed them sorely (my partner was feeding and watering them). After quite a while nuzzling with my critters, I got the idea that it might be soothing to smoke some of the weed I had stashed away.

It was great while I was at home, but the closer I got to the hospital the worse my paranoia became. Surely the nurses would be able to tell. It felt like high school all over again—trying to hide my red eyes from my teachers—except, unlike high school, there’s no way to escape if you’re having a bad trip. And if there’s one place you’re nearly guaranteed to have a bad trip, it’s in the hospital. I buried myself in a book until the worst of it passed, and didn’t make that mistake again.

You’re living in a fishbowl

Like any confined space where random humans are thrown together to coexist, a fishbowl environment develops. With little privacy and few distractions to while away the hours, it becomes incredibly easy to get caught up in the daily drama of the ward. As a people-pleaser, I’m always trying to ingratiate myself to others. This occasionally comes with a lack of tact: during my second hospitalization, I befriended an angry young man, who I thought had a good heart. He had some serious issues with women though. He grew jealous over my long-term relationship. Tensions escalated until he stole some notebooks from my room. Though the notebooks were returned by the nurses, while he had them, he scrawled ‘bitch’ on every page. When I met with my psychiatrist the next day, I asked to be discharged.

The problem with getting caught up in others’ problems, is the focus then shifts from your own. I’ve met a lot of fellow patients who are delightful humans while hospitalized, and even made some long-term friendships, but your first priority has to be your health and yourself.

If time permits, do your research

When in crisis, it’s easiest to head to your closest emergency room (and you should); however, the closest inpatient mental health unit isn’t necessarily the one that’s going to best serve your needs. While psychiatric intensive care units are designed to get you through the short-term, it’s ideal to find a hospital that can refer you to some long-term mental health supports following discharge so you don’t get caught up in the readmission cycle. In 2018, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canadians over the age of 15 who had been hospitalized and discharged for mental health concerns faced a nearly 13 per cent chance they’d readmit with those same health concerns within 30 days.

If you can’t find a crisis care centre that can connect you to long-term supports, take initiative to find continued support following discharge. Social service and mental health agencies often fill important gaps in an overburdened and under resourced mental health care sector by offering low-barrier or barrier-free mental health services (shout out and thanks to Woodgreen Community Services).

Plan ahead if possible. Between my second and third psychiatric admissions, I visited a friend at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto. As we caught up over Tim Hortons coffee—a rare treat in the ward, which only stocks decaf—I marveled at the level of care the hospital provided and the long-term supports available. I made a mental note that the next time I was in crisis, CAMH was where I was heading. I don’t think I need to tell you where I ended up for my third hospitalization.

Know your forms and your rights

In Toronto, where I live, psychiatric hospital admissions are regulated by the Mental Health Act of Ontario. At any point during a mental health admission, even if you arrived at the hospital voluntarily, you can be placed on something called a Form.

A Form 1, according to the Mental Health Act, is an application by a physician for a person to undergo psychiatric assessment to determine whether that person needs to be admitted for further care in a psychiatric facility. Once signed, a Form 1 is effective for seven days and provides the authority to transfer the person to a psychiatric facility where they may be detained, restrained, observed, and examined for no more than 72 hours.

A Form 3 is often signed after a Form 1 has expired, and the signing physician still feels you need care but are unlikely to stay at the hospital voluntarily. Once signed, a Form 3 classifies you as an involuntary patient that cannot leave the facility for a period of no more than two weeks. If after two weeks, the physician believes you still require care, you’ll be signed to a Form 4, which can last from one month to three months.

My advice is to willingly bite the bullet on a Form 1 if ever confronted with one. If you make a fuss, you’re more likely to be restrained and less likely to be given the option to stay voluntarily once the 72 hours has expired. The first time I sought out mental health treatment, I came to the hospital voluntarily without making an attempt on my life; however, I fought being placed on a Form 1. The admitting psychiatrist signed me to a Form 1 and a Form 3. I was shuffled between the closed side of the ward—the section of the unit for severe cases of mental illness (many patients were nonverbal)—and the open side—where I felt I belonged. I went through most of my stay without privileges before being discharged due to overcrowding. A patient who arrived at the same time as me and also came in voluntarily, but didn’t fight being Formed, went to the open side of the ward right away. They had privileges for the duration of their stay and were discharged as soon as they asked to be.

There’s also the possibility you’ll encounter a Form 2, which allows a family member to request a justice of peace to dispatch police officers to take you to the hospital. People I’ve seen come in on this Form seem to have to wait longer for privileges or the option to stay voluntarily.

If you feel, at any time, that your rights as a patient have been violated, you can contact the Psychiatric Patient Advocate Office.

You could be re-traumatized

It might seem counterproductive that a place you go to when you’re in crisis is so rife with possibilities for re-traumatization, but alas it’s true. It’s important to understand what seeking crisis mental health care treatment often means. You’re turning your wellbeing over to an underfunded and over-utilized institution and, depending on your admission status, relinquishing your ability to leave the hospital of your own accord. This can make receiving care extremely frustrating, even horrifying, and has turned me off of seeking help for years at a time. But it’s not just the absence of self-determination that can traumatize. In an inpatient ward, you’ll hear stories of human suffering more devastating than anything you’ve encountered. You’ll get a first-hand look at medical inefficiency. Even the lack of fresh oxygen and natural light can send a person right to the edge.

In my experience, the more agency I’ve been able to retain, the more privileges I’ve had access to, and the more I felt like I had an active role in my healthcare, the less likely it was I’d walk away from inpatient care with lasting fear. Though not all circumstances will be under your control, I hope the tips above will make your inpatient experience a lot more comfortable than my early ones.

Please keep in mind nothing on this list should deter you from seeking inpatient mental health treatment when in crisis. Being uncomfortable or even experiencing trauma while hospitalized is still a far better alternative to taking your own life or seriously injuring yourself. But, in a health care system that prioritizes treatment over prevention, is sorely underfunded and, in many respects, under-researched, you’re going to have to deal with some necessary evil to get the help you need.

If you’re in crisis, please contact emergency services, Crisis Services Canada at 1-866-456-4566 or crisisservicescanada.ca, or First Nations and Inuit Hope for Wellness Helpline at 1-855-242-3310 or hopeforwellness.ca.

Mad History

This issue: Deinstitutionalization in Toronto

Beginning in the 1970s, a new approach to dealing with overcrowded, underfunded, and understaffed mental health asylums swept across North America—deinstitutionalization. The idea behind the concept was to release psychiatric patients to reintegrate into society with the help of community-based care. Up until that point, mentally ill were typically housed in asylums that were segregated from the general population as mental illness was little understood and under-treated.

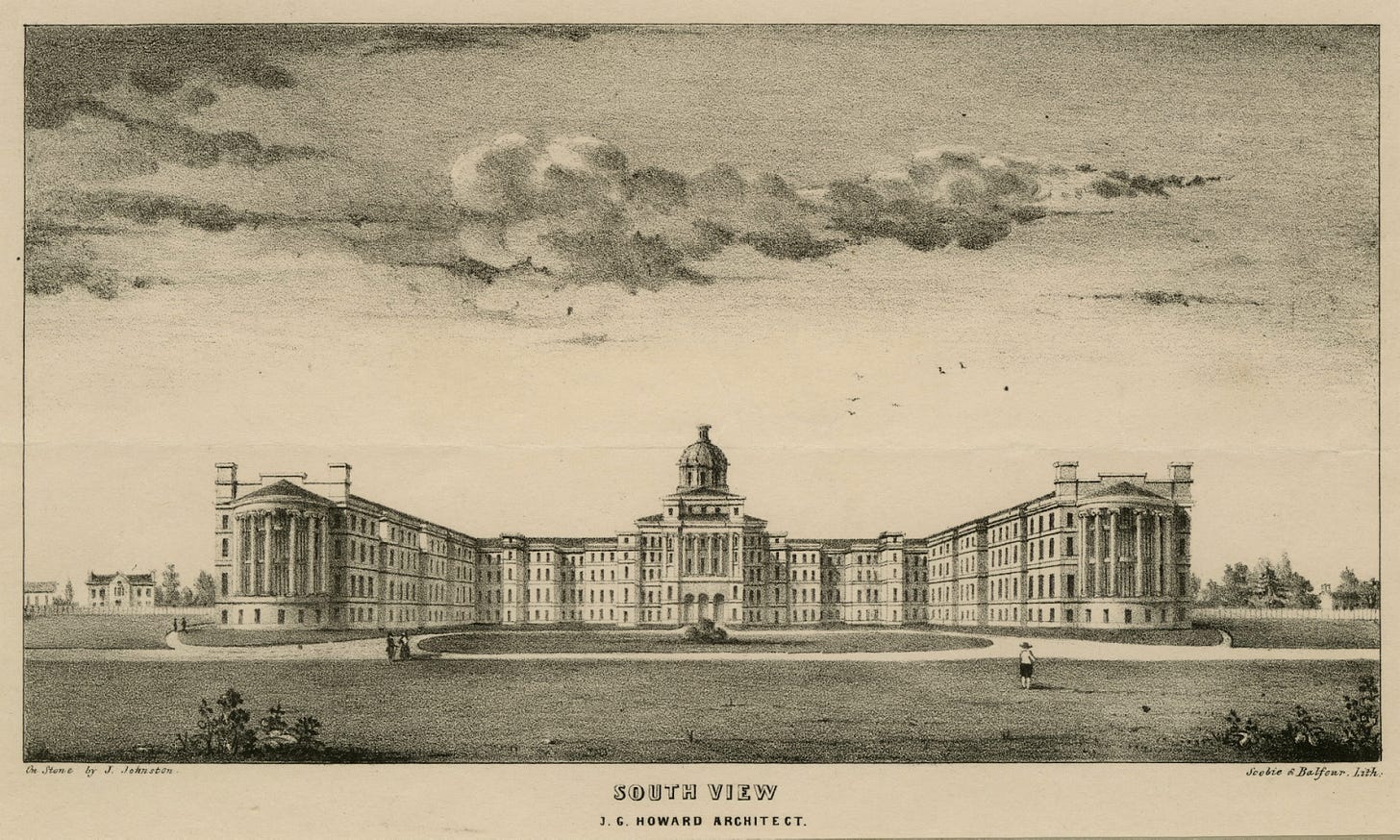

In Canada, the largest mental health facility during deinstitutionalization was located on Queen Street West in the neighbourhood of Parkdale. Operating under a variety of names since 1850, by the 1970s, the Queen Street Mental Health Centre (as it was then known), had become so overcrowded, understaffed, and faced such declining standards that, “pollution blackened its white brick walls.” The nearby Lakeshore Provincial Psychiatric hospital closed its doors in 1979, releasing its patients into the community. By the early 1980s, under the direction of the provincial government, thousands of patients were discharged from the Queen Street Centre.

While deinstitutionalization sounded good in theory, Parkdale had very few community care policies in place for newly discharged patients who had moved into its rooming or boarding houses or out onto its streets, since there were so few official group homes in the area. In Landscapes of Despair: From Deinstitutionalization to Homelessness, authors Michael Dear and Jennifer Wolch write that deinstitutionalization was, “a policy adopted with great enthusiasm, even though it was never properly articulated, systematically implemented, nor completely thought through.” As a result, Parkdale became a microcosm of poverty, untreated illness, and the effects of stigma. As recently as 2000, the neighbourhood was described by the Globe and Mail as, “a neighbourhood rife with poverty, drugs, and prostitution… to broken glass and wild screaming on the street at night. The prostitutes strolling down the sidewalk. The drunks splayed on the grass.” Instead of being seen as people in need, Parkdale’s deinstitutionalized residents were seen as dangerous and inconvenient.

Recommended Reading

For this issue, I’m going to do something I typically have a lot of trouble with: promote my own work! On January 11, 2021, I’ll be discussing, “Kids in Crisis,” a reported feature essay about suicide in Canadian children under 12 years old during Broadview Magazine’s National Online Reading Club event. The piece should be online shortly but, in the meantime, you can find it in the January/February 2021 print edition of Broadview Magazine.

Thank you for reading. Sign up to get this newsletter in your inbox.